Expanding Your Musical Language by Moving Beyond Typical Jazz Harmony and Song Form

This article is a lesson that comes to us courtesy of world-renown saxophonist, Jon Gordon, and also appears in his book, Foundations for Improvisors.

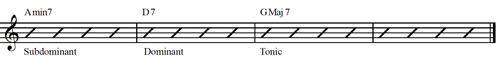

For nearly all jazz improvisors, the chord progression that is most familiar is the two-five-one (ii-7, V7, I), which is the basis of be-bop harmony. However, as we learn to expand our harmonic knowledge, we learn that harmonies are not always easily defined (e.g. Wagner’s prelude to Tristan and Isolde), and often move in ways other than sub-dominant, dominant, tonic.

First, let’s try to review and understand a bit more about functional harmony. Subdominant refers to a chord, often a ii or IV chord, which leads to or sets up the dominant chord. The dominant chord, often a V7, is thought of as the one with the most tension and therefore, the most impetus towards the I chord, which is considered the release of that tension, and called the tonic. In classical terminology, if the IV chord resolves to the I, which is common in rock and blues, it’s called a Plagal cadence – and can also be thought of as the “Amen” cadence.

This idea of sub-dominant to dominant to tonic can be and often is expanded in many ways. For example, D7 will usually resolve to G (major or minor). However, in classical theory, if that D7 resolved to an E minor, it would be considered a deceptive cadence. Depending on the key center you’re coming from (in this case G), if that D7 resolved to Eb or C#, these would also be considered deceptive cadences, as would anything other than a resolution to G. Many of us have come across these kinds of harmonic sequences in the past, but perhaps used different language to think about them.

Obviously many tunes played by jazz musicians extend the ii-V’s for 4-8 measures before resolving them to a one chord. Tunes such as “Honeysuckle Rose”, and “Woody n’ You”.

Also, many pre be-bop era tunes did not rely as heavily on the ii-V-I progression and often simply cadenced V7 to I, or moved between various dominant chords. The traditional 12-bar blues is a perfect example of this, as is the tune “Limehouse Blues” or Jelly Roll Morton’s “Tiger Rag”.

But when you look at and analyze certain music written and played by jazz musicians, it expands the idea of functional harmony even further. Take some of Monk’s music for instance. “Epistrophy” stays on a I chord (minor) for the first four measures of the bridge after alternating dominant chords on the first two A-sections:

- Db7 – D7 for 4 bars

- Eb7 – E7 for 8 bars

- Db7 – D7 for 4 bars.

You could also look at the first dominant chord in the A-section as the tonic, as we do on a blues, but the harmonic movement is very different in this case. Also pieces like”Skippy” and “Monk’s Dream” used dominant chords in a way that no one else did. (By the way, “Skippy” is a line written over a brilliantly re-harmonized set of changes that Monk wrote over “Tea for Two”. And the dominant chords move one-per-beat towards the end of the last A-section. Very challenging to play on!)

Miles Davis’ “So What”, which is simply D minor on the A-sections and Eb minor on the B-section, is a perfect example of what began to be called modal music, and shaped much of the music written and played from the late 50’s to the present time. A piece like “Epistrophy” might also be considered modal.

Other pieces by Miles, Bill Evans, Coltrane and others stretched and transcended the previous ideas of standard harmonic movement. Some tunes that I’d like you to learn that fit this category include “Naima”, “Inner Urge”, “So What” and “Impressions”. And in particular, Wayne Shorter’s “Iris”, “Nefertiti”, “Fall”, and “E.S.P”.

It’s not that tension and resolution are not taking place, obviously they are. However, these pieces are going about that process in ways that were not previously done. You will quickly find that some of your vocabulary that worked on standards and earlier jazz compositions will not work as well over these kinds of pieces. In short, ii-7 V7 I’s can no longer be the sole basis of your vocabulary.

The Role of Form

I also want you to consider form. As you may have noticed, many standard American songs were written using the A-A-B-A form. They’re often 32 bars, though some may have an extended last A-section (like “I Got Rhythm”).

There are also 32-bar tunes like “Days of Wine and Roses”, or “Like Someone in Love”, which could be interpreted as “A-B-A-B prime” (“prime” referring to a similar but somewhat different take on the earlier material). “Limehouse Blues”, also 32 bars, could be interpreted as A-B-A-C. Blues as we know it today is usually a 12-bar form, though it’s not limited to that form, and in it’s earlier incarnations was often not 12 bars.

Also, many of the great standard songs that are played by jazz musicians have verses, usually played only once at the beginning of a piece. These obviously expand the form and often set up the rest of the piece brilliantly, as in Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust”, Strayhorn’s “LushLife”, Monk’s “Round Midnight”, the standards “Tea for Two”, “A Foggy Day”, and others.

But a piece like Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes”, for example, which is three 9 bar phrases, is unlike almost any other standard or jazz composition before it. Or Monk’s tune, “Boo Boo’s Birthday”, which is two 8 bar A-sections followed by a 5 bar section (or perhaps a 3 bar B-section and 2-bar last A), is clearly another brilliant and original take on form. Much of this information may be evident to many students, but it’s very important to be aware of and to take into consideration as an improviser, composer or arranger.

Lastly, I think now is a good time to mention that while this article deals with many post be-bop concepts, I strongly urge you to work backwards in time and music history as well as forward in the process of learning and appreciating this music. Regardless of your direction or aesthetic, you need to know the history of your instrument. And by going both forward and backward in time with your studies, you will also certainly learn a great deal about form and harmony, as mentioned above, as well many other things about time, your instrument, and the music.

And if you’ve not yet checked it out, you’ll be amazed at Duke’s “The Clothed Woman”, Bix’s impressionistic, “Clouds”, Hawkins’ use of chromatic passing tones on his classic3recording of “Body and Soul”, or Tatum’s uses of polytonality. Notice the forms of the pieces being played, and be aware of the different harmonic conceptions from ii-V-I’s. Duke’s music, the Scott Joplin rags, Jelly Roll Morton, et al.

So, along with doing all of the suggested listening, I want you to learn all the tunes mentioned in this lesson. You should probably also be investigating other pieces not mentioned specifically by the aforementioned musicians- they’re all prolific!

I also want you to write two contrasting pieces that each have forms that are somewhat unusual (e.g. A, B, C, D, 10 bars each), and that utilize harmonies that stay away from ii-7, V7, I language that we’ve become accustomed to.

For example:

- Try to avoid a direct V7-I resolution and only use “deceptive cadences” on one of the pieces.

- On the other, try to write something in the style of Scott Joplin or Jelly Roll Morton.

- Then try to play over what you’ve written.

You will teach yourself quite a lot and expand your musical language and thinking over these different options on form and harmony.

Be a part of Jon Gordon’s new Artishshare project! You can pre-buy the CD, or become a producer level supporter of the recording. There are also offers designed specifically to bring students into the process of the creation of the CD. Click here to check out the project!http://www.artistshare.com/Projects/Experience/64/506

http://www.artistshare.com/projects/Index/64/195

http://www.jongordonmusic.com