A Checklist For Practicing Technique to Develop Musicality

During my 45 years of playing the saxophone, 25 of which have included teaching at the university level, I’ve developed a teaching philosophy that boils down to two pretty simple things:

During my 45 years of playing the saxophone, 25 of which have included teaching at the university level, I’ve developed a teaching philosophy that boils down to two pretty simple things:

- Help students develop strong fundamental musical skills (instrumental technique that is relaxed, flowing, and confident; rhythmic/metric integrity; fluency in theory and harmony; broad knowledge of musical styles/cultures/histories; etc.)

- Expose them to frequent and varied musical examples, approaches, and concepts to build a broad and well-informed musical vocabulary.

At that point, sit back and let them figure out where they want to go utilizing the tools they’ve developed, offering constant support along the way.

For years now I’ve given students in my studio a one-page handout I call “The Checklist” (downloadable for free here). It includes no “licks” or melodic patterns. Arguably, it provides nothing in the realm of what-to-play when improvising.

Instead, it presents a systematic approach to acquiring the physical memory necessary to execute what-to-play – regardless of the source of inspiration. The Checklist is intended to ensure internalization of the foundational material, entered into one’s physical memory step-by-step, and required to facilitate successful and effortless instrumental execution.

The goal is to create a comprehensive technical foundation that then allows one to focus primarily on creativity and the musical impulses of the moment.

Think of it as a requirement rather than an elective. There are countless things that you can and must do electively to become a complete musician. But there are some things that are simply required, that need to happen all along the way, regardless of – and in parallel with – all of the electives.

Often when performing or recording, it’s as if we have blinders on and suddenly can’t even access the material that felt so good just moments ago in the practice room. As it turns out, you must address these technical requirements more than one would think.

To really overcome the blinders, you must practice what almost feels like too much at times in order to create the kind of physical memory necessary to allow your ideas to land.

The truth is, there are no shortcuts other than learning to practice productively and efficiently. And there is a LOT of work to do, on multiple fronts. So in keeping a predefined list of things to practice, you are employing an excellent method to keep yourself on track.

Most of The Checklist relates to working on several important scale families in all 12 keys:

- major, (ascending)

- melodic minor

- harmonic minor

- harmonic major

- diminished

Things start simply enough. But through an additive process where each new exercise builds squarely upon the previous ones, they, soon become rather complex.

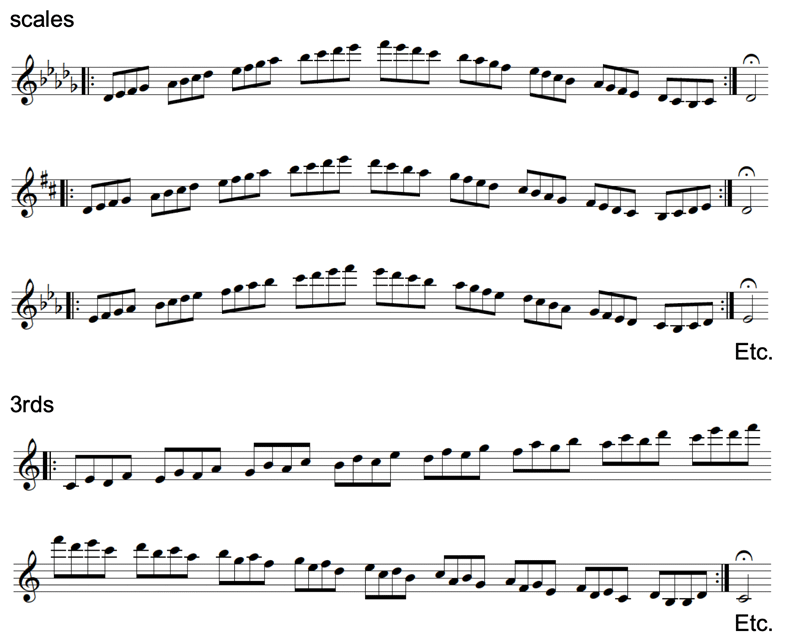

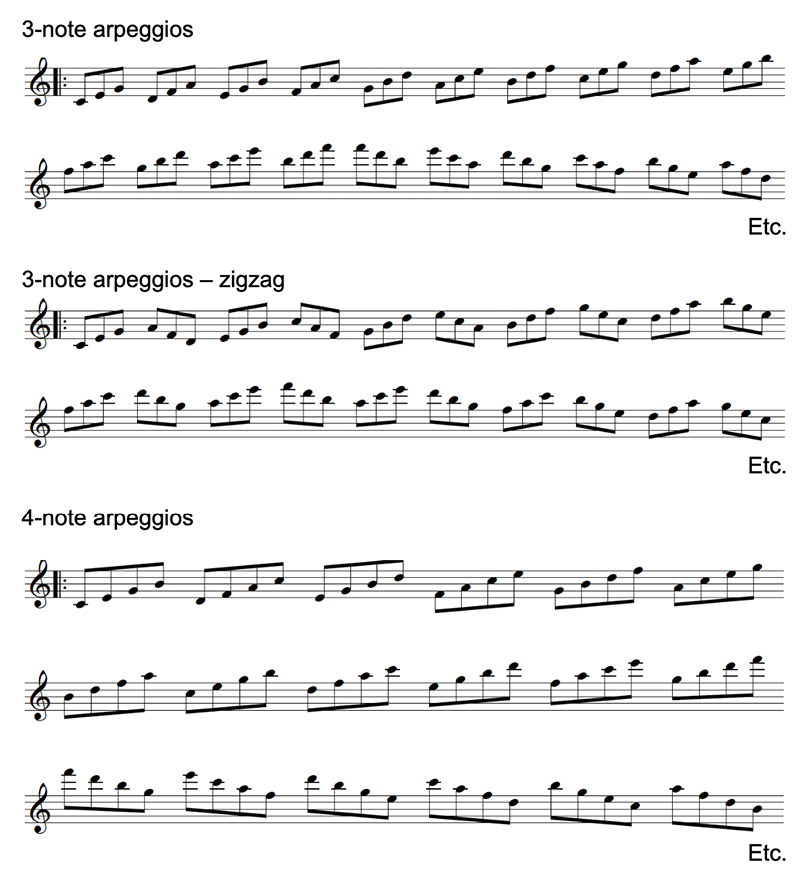

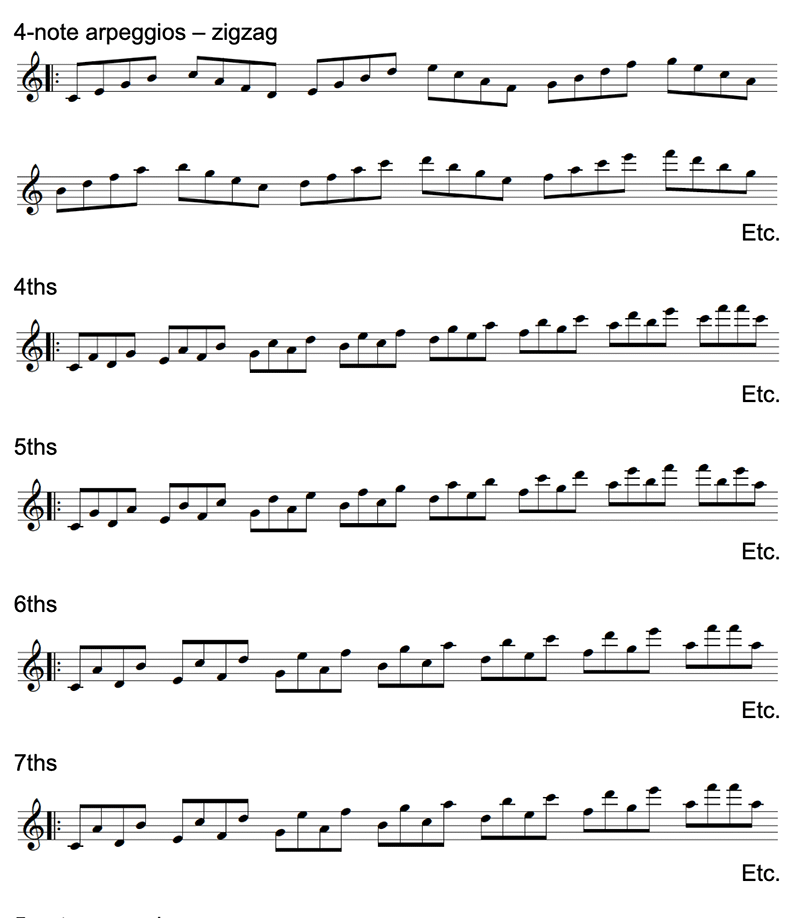

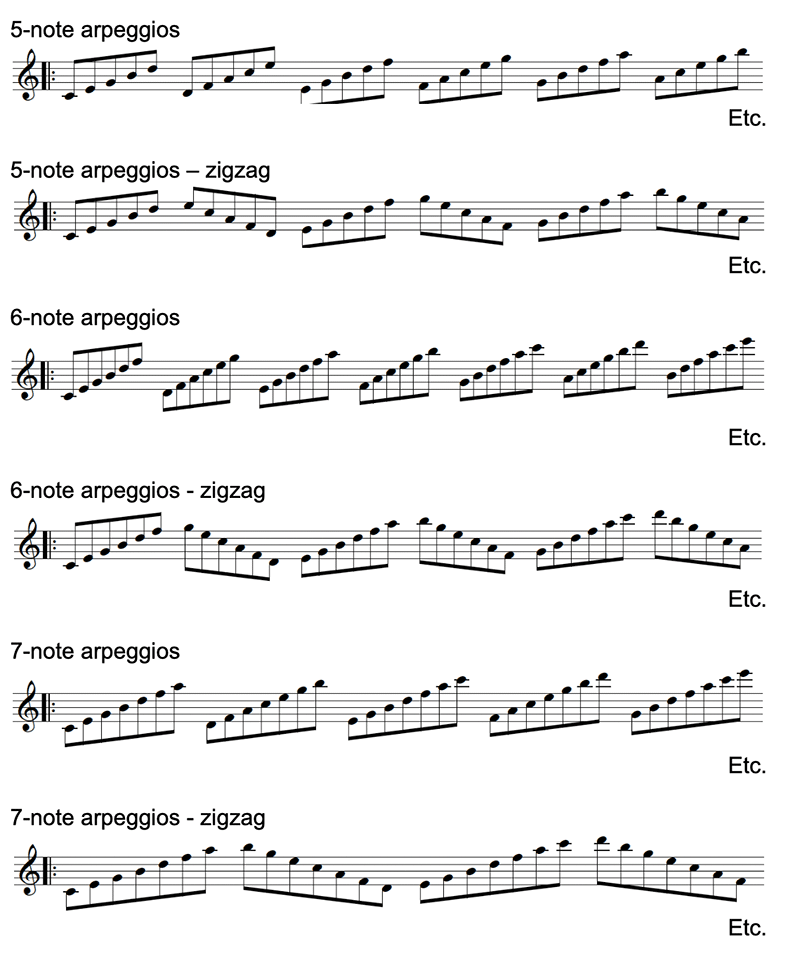

Below are the exercises to take through each key or scale, always over the entire range of the instrument.

Note that the first example of scales is transposed in 3 keys to offer an example of adjusting practice material as needed to span the entire range of the instrument (whatever that is for you at this time).

Click here to download a more readable and printable PDF containing the exercises below.

Yes, it’s a lot! But imagine how well you’ll know your major (and other) scales once you have all of that internalized in all 12 keys over the entire range of the horn. The Checklist provides a visual reference and organizing document for taking on this extensive series of tasks.

And know that the reason we practice scales and other basic material (into the ground) is not so we can just play scales when improvising. Rather, over time, they create a foundation of physical memory that has mapped and “pre-navigated” so many possible sequences of notes that whatever idea you’re trying to execute, you’ll already have muscle memory (or memory of something very close) to support its execution. Knowing something should happen is very different from getting your body to make that thing happen, and reducing that latency is a major goal/function of this kind of practice.

When you’re hanging out with friends and listening to music, or have that once in a lifetime live concert experience that just changes everything, your conception of music can change in an instant. Before and after.

For me it was Ronald Shannon Jackson in Portland Oregon in 1985. Eric Person was playing alto and baritone in the band and it changed everything for me.

From one moment to the next, you can experience these musical revelations that cause you to grow in leaps and bounds conceptually and aesthetically. But if you can’t execute what you hear/think, none of that matters very much until you can.

So while your mind and heart are figuring out what kind of creative artist you want to be, make sure that every single day you do the thoughtful, careful, meditative technical work that needs to be done so you are fully ready when the inspiration hits you because hearing something in your head is very different than feeling it in your fingertips.

Just remember, if you’re working on something and you ask yourself, “have I practiced this enough?” The answer is probably, “no.” Happy practicing!

March 5, 2024 @ 8:24 pm

Hello,I just read your article on the check list it was quite helpful I believe it will help me advance in my scales with my alto and tenor sax.johnb