A Guide to Improvising in Odd Time Signatures

There seems to a be a common idea that improvising in odd time signatures is hard. When I come across a new time signature, I remind myself that it isn’t difficult – it’s unfamiliar. If you think 4/4 is easy, that’s likely because you’ve spent significantly more time playing songs in four, making it familiar and comfortable.

There seems to a be a common idea that improvising in odd time signatures is hard. When I come across a new time signature, I remind myself that it isn’t difficult – it’s unfamiliar. If you think 4/4 is easy, that’s likely because you’ve spent significantly more time playing songs in four, making it familiar and comfortable.

I say that because I believe the best way to learn to improvise in odd times is to simply do it. The more I’ve played music in odd times, the more comfortable I feel. I make it a point to play a couple songs in a couple different time signatures every day in my practicing in order to continue to deepen my familiarity. As much as I can, I play songs in odd times with other people, too. And don’t wait until you feel “ready” – playing with other people will be an important part of helping you feel ready.

Before we jump into it, you may be wondering what to play along with. I like using iReal Pro as you can easily change the time signature of standards, change the tempo, and loop sections. Sometimes, I’ll write out music in programs like Finale or Garage Band. When I can, I also love playing along with actual recordings. Unfortunately, though, no one has yet recorded every single standard in every single possible time signature. And of course, there’s always the metronome.

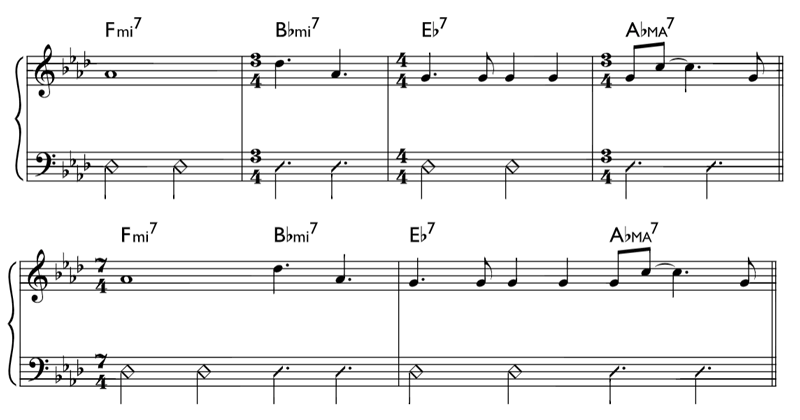

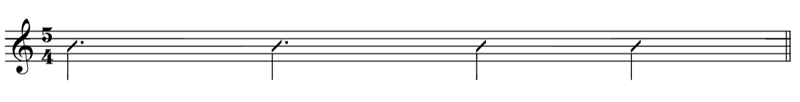

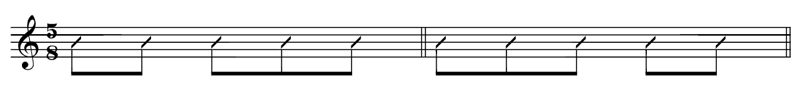

Let’s start with the two of the most common odd time signatures – 5/4 and 7/4. To begin, I find it helpful to understand the most common ways of breaking up these time signatures. 5/4 is usually played as 3 + 2 or two dotted quarters then two quarter notes. Just think about “Take Five.”

7/4 is usually broken up as 4+3 or two half notes then two dotted quarter notes. Joshua Redman’s arrangement of “East of the Sun (West of the Moon)” is a great example.

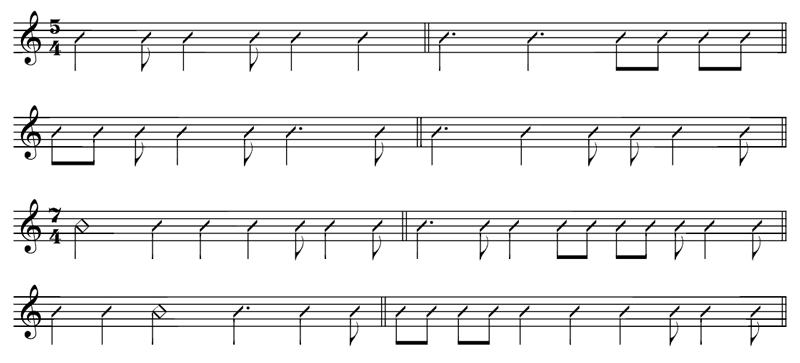

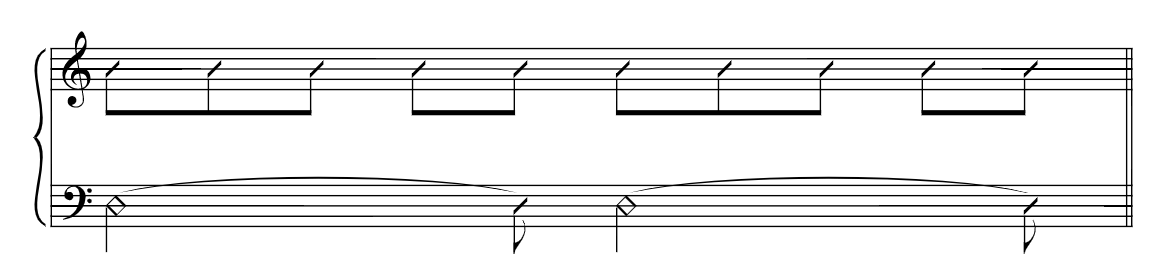

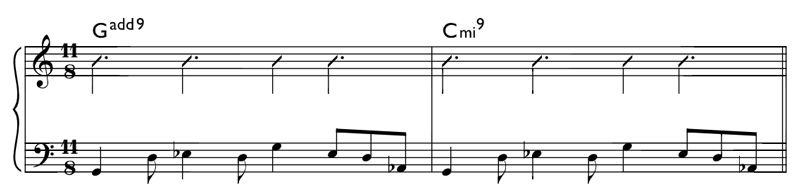

My first step is to only improvise with set rhythmic patterns. The goal is to build your rhythmic vocabulary for this meter. I start with the underlying ostinato, which you can find above for 5 and 7. Then, I work through other patterns. I’ve listed a few examples for both 5/4 and 7/4 below. Note how these clearly show the underlying ostinato. It’s important to learn to comfortably outline the ostinato in your improvising before exploring how you can blur the bar lines.

I allow myself to play any notes – though it’s often easier to keep notes simple until you are more comfortable with each of these patterns – as long as I’m using the exact rhythm.

Start by working through these one at a time. Take a tune you know really well and change the meter. Play a few choruses – or even just a few measures on loop – until you feel comfortable with the rhythmic pattern. Then, you move on to the next one. If you find you are having difficulty playing these rhythms, try clapping or singing them. Feeling the rhythms with your body can help internalize them.

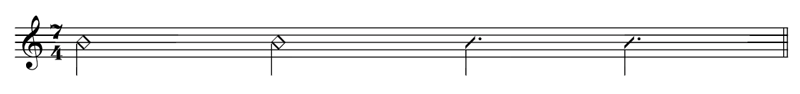

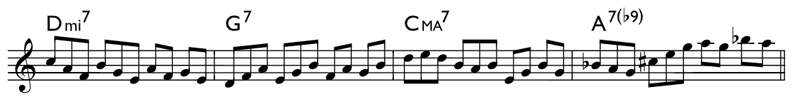

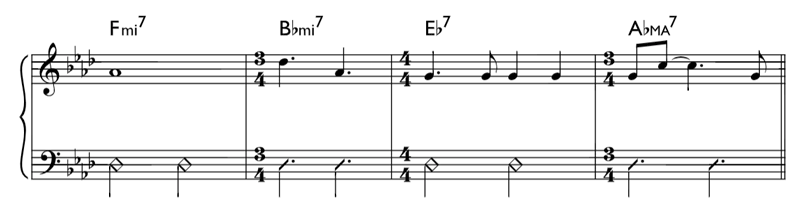

As you become more comfortable with a pattern, start to explore different note choices. Remember to keep in mind how you choose notes normally, meaning 3rds and 7ths are the most important notes, 7ths resolve to 3rds, outlining chords, and so on. Here’s an example of something I might play when practicing 5/4. Notice how it sticks close to the chord tones. Starting simple is best until you feel comfortable.

You can even come up with your own rhythms to use. Something that helps me as I’m shedding in this manner is to think of the smaller groupings that I’m already familiar with. Chances are you’re more familiar with 3/4 than 5/4 or 7/4, so think about what rhythms you would play in 3/4 during the groupings of 3. When the groupings are 2 or 4, think about playing in 4. Ultimately, as you grow more comfortable with odd meter, the goal is to have 5 feel like 5, 7 feel like 7, and so on.

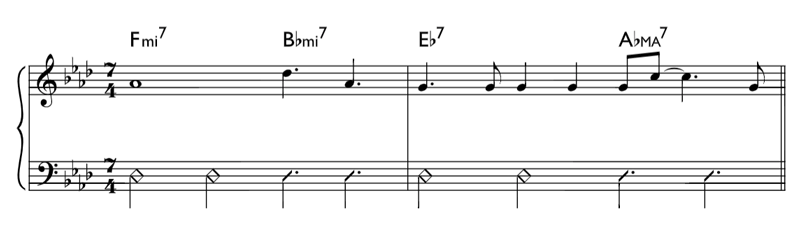

An easy way to expand upon some variations you already know is to break longer notes up into 8th notes. Playing lots of 8th notes isn’t always the most rhythmically interesting possibility, but again, the point is to build our comfort level. The key here is to still show the underlying ostinato in a natural way, as opposed to playing your 4/4 language and trying to accent different notes then you normally would. Notice in this example how the groups of three 8th notes are clearly a three-note figure, and the groups of two 8th notes make sense as a pair.

As you become familiar with some set rhythms, start to explore how you can mix them up. This will start to increase your flexibility in and comfort with these time signatures. At this stage, though you can do this at any stage, you may find it helpful to write out a solo. Write and learn a solo over one chorus of a tune using a mix of the rhythmic patterns you’ve been working on. When I do this, I trade choruses with myself, going back and forth between my written solo and an improvised solo, trying to get my improvised solo to be better than the written solo. This is one of the many things I learned from my mentor Diego Rivera.

Remember that listening is always important for music. Listening to music in odd meters will help you internalize the feel, as well as provide a resource for other ways of playing over and approaching odd times. Here are a few examples I like:

Sweet and Lovely – Bobby Broom (5/4)

Moment’s Notice – Ari Hoenig (7/4)

Comma – Ron Miles (7/4)

Crooked Creek – Brian Blade Fellowship (5/4)

Kopi Luwak – Alan Ferber (Various)

Gold Rush – Etienen Charles (7/4)

Taking Flight – Tony Lustig (5/4)

And get out there and play in odd time with other people! The more you play, the better you’ll feel.

That’s pretty much my approach to learning how to improvise in odd times. Remember that this process isn’t linear – you’ll find yourself jumping around between steps, and that’s ok. And, talk with other people about how they approach odd times – there’s no right way.

Below are some other thoughts I have around odd time signatures that may also help as you explore odd times.

I focused on meters with the quarter note as the beat, but an important consideration is whether or not the beat is a quarter note or an eighth note. For example, the common ostinatos found in 5/8 are different than 5/4. In 5/8, I’ve come across 3 8ths + 2 8ths as well as 2 8ths + 3 8ths.

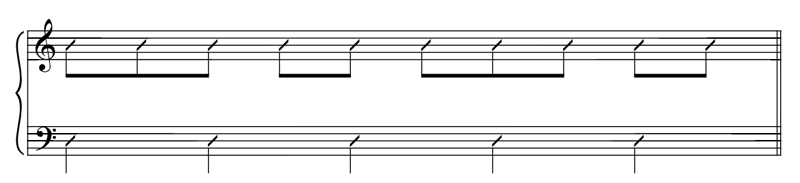

However, if you put two bars of 5/8 together, you can think of it as 5/4 that’s split evenly in half.

This is where things can get really interesting. Do you feel the beat as quarter notes, resulting in 5/4 with the measures split in half?

Do you feel the pulse as an uneven pulse of dotted quarter and quarter alternating?

Or do you feel the pulse as single beats divided into 5?

Perhaps this seems overwhelming, but really there’s no right way. I think it’s important to be able to feel odd meter in different ways as that allows you to be more flexible both in your own improvising and with adapting to how other people feel the beat.

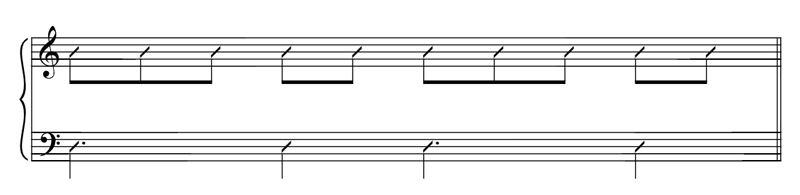

Another consideration is what is actually defined as a measure. This is most important when you’re playing a standard in an odd time. I like playing “All the Things You Are” in 7, so let’s take a look at the first four measures of that song.

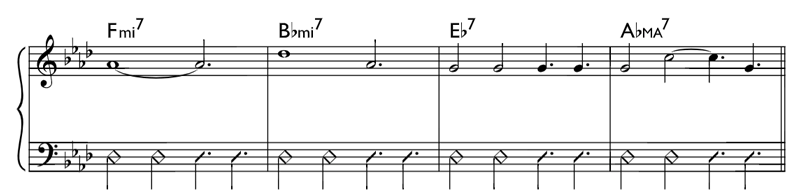

The way I usually play it is actually 4/4 & 3/4 alternating. This is what it looks like, with the melody written how I might phrase it.

However, I’m more likely to write it 7/4, though, as I find that’s easier to read.

But you can also play it where every measure truly becomes a measure of 7/4, like this:

From a rhythmic standpoint, both will sound the same and the way I phrase would be the same. What changes is the harmonic rhythm. The harmony in the first example basically moves twice as fast as the harmony in the last one. I’ve come across the first example more often, but it’s important to be aware of both possibilities. Again, there’s no right way, but you want to make sure everyone is on the same page.

On a related note, there are so many possibilities with how you can play standards in odd times. I’ve played “All the Things You Are” in 3/4, 4/4, 5/4, 6/4, and 7/4. To me, they all feel great and natural in their own unique ways. You’ll find some songs work better in some meters than others. Just start experimenting!

I started with 5/4 and 7/4, but there are many, many, many more types of odd meter you’ll encounter. However, I find the more variations you learn, the easier it gets to learn new types. That’s because you can almost always breakdown odd meter into pieces you’re more familiar with. On my album, I wrote a song that had me soloing in 11/8. When I started preparing for the recording session, I had never played in 11 before. So, when I went to shed it, I broke down what was actually going on here. The underlying ostinato in this 11/8 is 3 + 3 + 2 + 3. I decided to split that into two halves in my mind. 3 + 3 is really just playing in 6/8 or using all triplets. I’ve done plenty of that. Ok, that’s easy enough. 2 + 3 is a 5/8 pattern that I had played before quite a bit. So, I really knew everything I needed to know to solo in 11/8 – I just had to start doing it! I still went through my process above of determining a few set rhythms to play over the ostinato. I did this for maybe 10-15 minutes a day in the 1-2 months leading up to the recording, and by the time we got to playing, I could mostly feel the 11/8 rather than think about it. After a week’s tour and many hours of rehearsing, 11/8 was feeling natural.

One last thought of mine. Be musical. Please. Don’t play in odd time just for the sake of playing in odd time. If you force it, it won’t feel good. I don’t write songs in odd times – my songs just happen to be in odd times. When you play standards in odd times, approach as another element of music to explore. When you open the doors to odd time signatures, you’ll find that there is an incredibly vast world of musical possibilities to explore.

December 8, 2021 @ 12:59 am

Thank you Joseph for this really well explained post!

I’m studying ‘Take Five’ this month in a jazz practice group and I’m looking for information on how to improvise over 5/4.

Your suggestions for diving deeper into this are really easy to digest and follow.

Your Sextet sounds amazing. I loved listening to it.

December 8, 2021 @ 7:46 am

Hi Amelia, I’m so glad you found this helpful! I really appreciate you giving this a read and listening to my band.

Take Five is a great song for 5/4 – if you haven’t already, I highly recommend studying Paul Desmond’s solo on that. It’s one of the first ones I studied actually and very helpful for getting more comfortable with both that song and playing in 5!