A Musician’s Guide to the Art of Creative Practicing

I believe that jazz music is one of the most intellectually and artistically demanding paths on which a musician can be. Technical chops and pyrotechnics that have historically been part of jazz improvisation are still an intrinsic part of the music, and the skill set needed to learn an instrument well enough to navigate the harmonic challenges of jazz with a good time feel still takes years of practice. But at this stage of my career, much more so than impressive technique, I find greater satisfaction in encountering beauty and mystery in both what I listen to and in what I pursue in my personal performance.

At the outset, I want to stress the importance for any musician to pursue the technique that this music requires. However, what I want to do in this article is to suggest an alternative vantage point of practicing with different strategies to develop the chops and “pyrotechnics” for the specific purpose of serving as a vehicle for creating mystery and beauty.

Like many young musicians I went about acquiring technique and language by learning solos and then taking some of the lines through all twelve keys. But after amassing a certain amount of facility and language via this necessary discipline, I needed to know what to do with it. How do I use impressive technique in improvisation and make it musically meaningful?

As a musician one never stops growing and learning, and I recently have gone through a personal paradigm shift after immersing myself in traditional Irish music. On a surface level, the melodic and harmonic content of Irish trad seems limited when compared to the material used in jazz improvisation. A great deal of the traditional tunes is in only three major keys and their relative minors. While ornaments make use of chromaticism, the chromaticism that is so prevalent in bebop is generally not found in the melodic lines of the Irish trad tunes. However, in spite of these perceived limitations, I came to realize that “trad” music possesses a seemingly unlimited canon that is often based solely on the seven notes of either a Major, Mixolydian, or Dorian scale. Pondering this phenomenon has made me listen to and think about music with new ears and confront the self-imposed limitations that I have previously placed on music that stays within a narrow key range.

Irish music was originally played unaccompanied by a soloist or in unison in a group with the harmony creatively woven into the melodic line. This got me to think about and then experiment with the depth of possibilities contained within a seven-note scale. For musicians pursuing technical proficiency it is almost universally understood the essentiality of practicing a scale or a mode through the full range of the instrument in addition to incorporating different iterations such as diatonic intervals within the scale.

But so what?

Many method books contain much of the same information. What does one do with it? Is it possible to get beyond this digital organization of a scale and enter the arena of improvisation without preconceived notions of what is to be? I want to suggest three options that can be a gateway to fresh organization of the seven notes of a scale.

1. Irregular rhythmic coupling of diatonic triads.

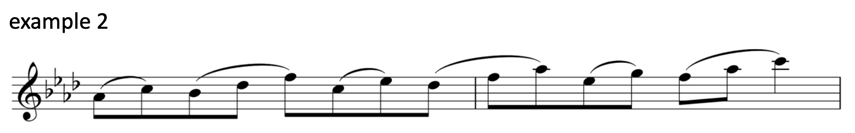

The following is the beginning of an example of what one might find in a saxophone method book of a diatonic chordal exercise in Ab major. It would be essential to follow this through to the end and play this throughout the entire range of the instrument.

The following example uses the previous diatonic chords but in groups of 2 notes and 3 notes in order to intentionally disrupt the predictability of the previous exercise in order to create interest. I suggest playing this and the following exercises throughout the full range of the instrument.

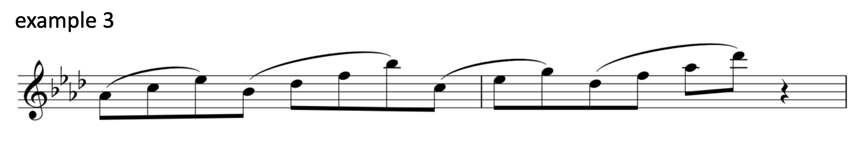

Similarly, this is an example of using groups of 3 notes and 4 notes used for the same purpose.

Note that this idea can be used both to realize different time signatures as well as giving a line a rhythmic punctuation in 4/4 time. The groups of 2,3, and 4 can be reordered to the extent of one’s imagination and desire to do so.

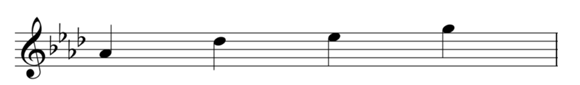

2. Creating a shape within the scale and carrying the shape diatonically throughout the tonality.

Here is an idea consisting of root, 4th, 5th, and 7th.

This shape possesses an intervallic structure starting with the root note followed by a 4th, a 2nd, and a 3rd. This pattern remains consistent as the scale ascends.

The shape can be any number of notes and any combination of ascending and descending intervals. The possibilities of shapes that can be created really are endless, limited only by imagination and time. I like the idea of practicing any shape in major, harmonic major, melodic minor, and harmonic minor.

3. Disrupting stock language that most practitioners of music based in bebop use.

The intent of this is to break up melodic patterns that perpetuate the idea of “this is how this has to be played.”

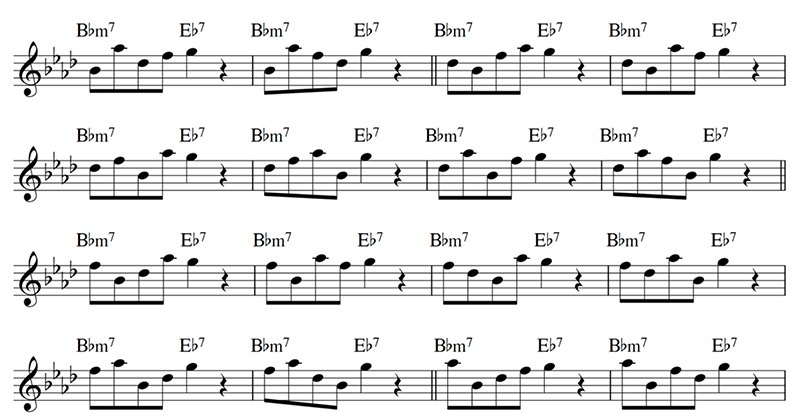

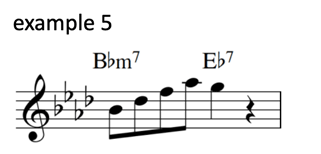

This is a stock gesture of a ii7-V7

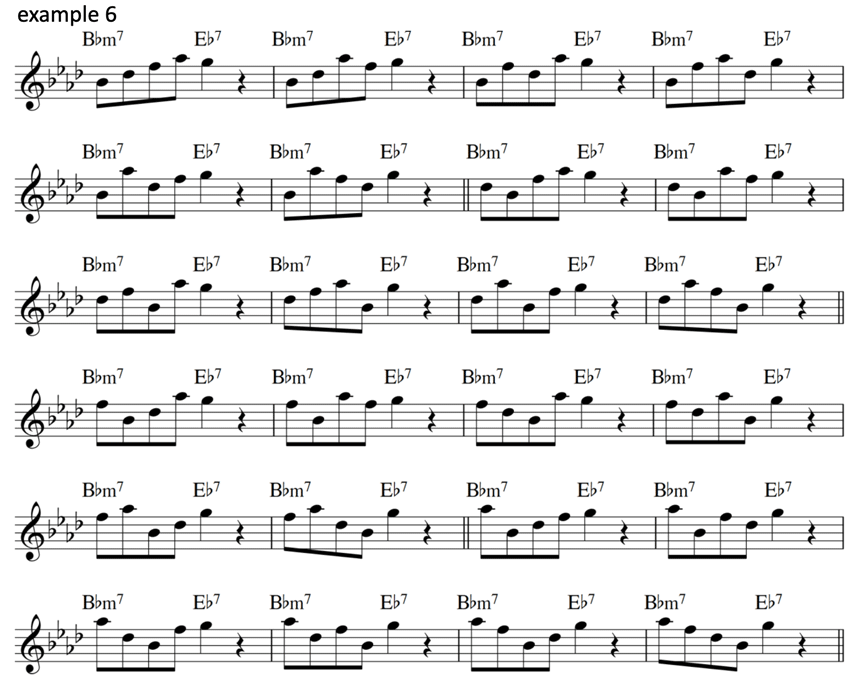

There are twenty-four ways in which the four notes of a 7th chord can be ordered.

The notes of this line can be reordered in the aforementioned twenty-four ways with the intent of providing a different approach to the same information.

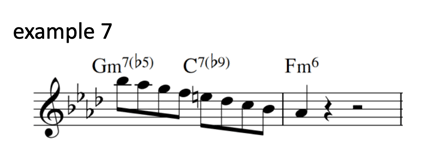

Here is an example of a typical bebop line using a harmonic minor scale to negotiate a minor ii7-V7-i6.

This is an example of applying the same concept of disrupting convention with the first four notes of the scale from the Bb.

The same reorganization can be done in this case from the Ab, G, and the F. You can then also apply the same idea to the last four notes over the C7, then possibly combine different iterations of the first four notes and the last four. It is an exercise designed to make you think.

What I want to communicate in this article is not found in the actual notes of the previous musical examples. These are not licks to be practiced and memorized, since not all of them are intended to sound good.

It is not necessarily helpful to play them all as this is not intended to be an exhaustive endeavor, which could be a soul crushing governor on the creative process. I am encouraging you to practice creativity. I want you to ask yourself questions like:

- “How many points of entry can I choose from as I improvise in a given tonality or harmonic structure?”

- “How many places can I go within a tune?”

- “How quickly can I execute what my imagination challenges me with?”

Use this as an invitation to cast aside the shackles that practicing deep in the shed can produce. I believe that through the process of exploration, the creative muscle will be thoroughly exercised. As you learn to trust your soul, mind, and ears, you will create the ability to encounter different options from which to choose – options that will lead you in your pursuit of beauty and mystery using effortless technique.