Learning the Vocabulary of Jazz, and Using it Creatively

To keep it interesting for myself, one of the things I did while writing The Jazz Saxophone Book, was to create what I called “Short Asides.” When something I was writing about sparked an idea that deserved a bit of a detour, I’d go ahead and write about it, and the Short Aside format helped me keep track of the larger picture.

To keep it interesting for myself, one of the things I did while writing The Jazz Saxophone Book, was to create what I called “Short Asides.” When something I was writing about sparked an idea that deserved a bit of a detour, I’d go ahead and write about it, and the Short Aside format helped me keep track of the larger picture.

In the Asides I discuss practical things like putting tunes together to make a good set, talking to the audience, whether there are ‘avoid notes’ or not (there aren’t!), and whether or not to play licks and patterns.

My answer to the question, “Should I play licks?” is:

Yes, if you can do it creatively.

Remember back in school when you learned vocabulary words in your English class? If your teachers were any good, they didn’t just ask you to memorize new words—they had you use them right away in a sentence. For example, let’s say your new word is ‘delicious.’ If you just wanted to get the assignment done with minimum effort, for your sentence you could write:

“The food was delicious.”

That sentence would at least indicate that you understand the meaning of your new word, and you can use it correctly.

If you had a little more imagination, and wanted to impress your teacher, you might try:

“The food I had at dinner last night was so delicious that I had a third helping.”

If you love language and get the idea that you can use words differently than the usual, literal way, you might try:

“The feeling of swinging was so delicious, I didn’t want to stop blowing, and took one too many choruses, resulting in the drummer throwing a cymbal at my head.”

And if you just couldn’t get enough of language, you might try inventing some new words, using ‘delicious’ for inspiration.

- Deliscous

- Deliscience

- Delisciosity

- Delicerati

- Deliscerance

Some of those words feel like they could be real words, and some don’t. It works the same way with musical language, and you have the advantage that the ‘words’ (licks) aren’t tied to a specific meaning.

All of the above steps are routine wordplay for people who love the language of jazz. How does that work in a musical context?

The big picture is:

- Learn a lick – add a musical word to your vocabulary

- Begin improvising with it immediately – try changing the word a bit – tinker with it.

- Try it out in some different contexts – use it in some sentences – try making some lines with your new word, and see if you can play them in time over a progression.

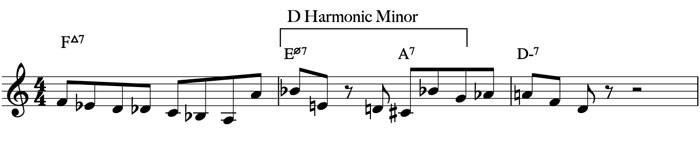

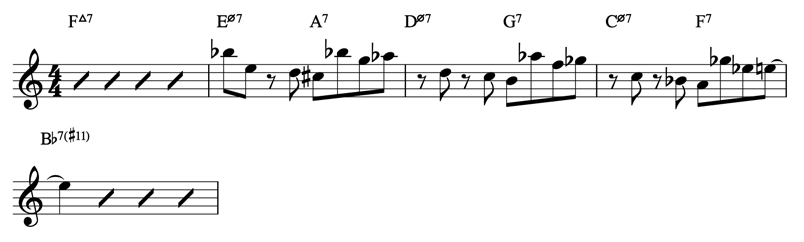

Here’s an example from Chapter 15 of the book. It’s part of the first phrase of Charlie Parker’s solo on “Confirmation.”

Here’s the lick:

And here’s a link to the recording, which is on a playlist of the examples cited in the chapter:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLvry3yORzD84Okh5In5rWRvrvTjAxXzjF

After learning to sing the line, I then try to play it in time, matching what I hear in my mind’s ear with what is coming out of the saxophone. If I’ve taken the time to learn to sing it accurately, I’ll know whether what I’m playing is a good representation of Parker’s line. Then I can play it along with Parker a few times, to confirm that I’m getting the feeling of it.

Instead of leaving it to chance whether my new word will bubble up into my improvising at some point, I can jumpstart that process by immediately starting to improvise with it.

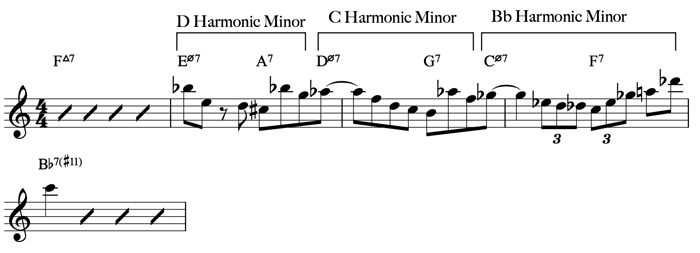

Here are a few ‘words’ of my own, inspired by Parker’s line:

Ok, we’ve found a lick we like the sound of and we’ve tinkered with it a bit. How can we use it creatively?

The following is an excerpt from the book that picks up the story from this point…

What I mean “using it creatively” is: if I just learn the notes of a lick, and then plug it in exactly the same way chorus after chorus, I will sound like I’m reading a script off a teleprompter, rather than conversing freely in a language.

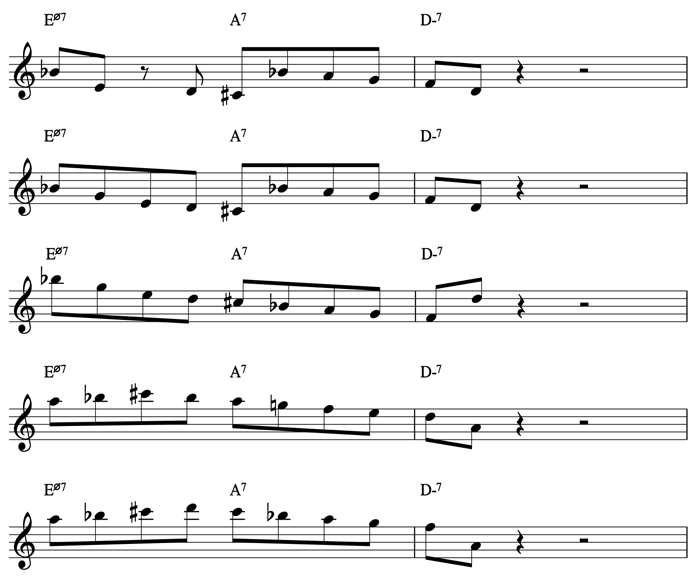

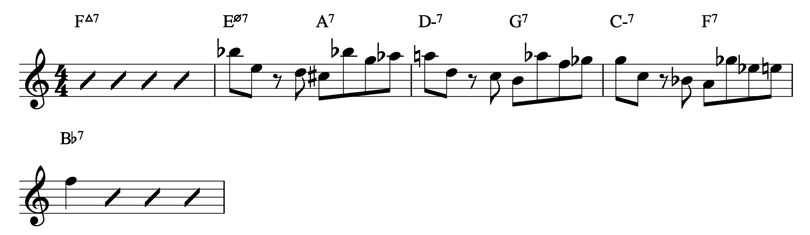

Let’s use the phrase we learned from Charlie Parker as an example. Here it is again, with the changes that come after it written in:

See how the changes after the second bar are following a pattern? It’s II-V’s going down in whole steps. The D-7 and C-7 chords are not half diminished, but that’s ok. We’re improvising, so we can make some decisions about that on the fly.

If I take Parker’s lick and transpose it for the next two bars, adjusting it for the natural 5th on the D-7 and C-7, it looks like this:

Try it. It sounds good, and the first time you play it, it will sound pretty smooth, like you have command of the changes. But if you play it again the same way on the second A section, it’ll sound like something you’ve worked out over the changes, not like something you’re imagining and pulling off in real time. You could be creative with the harmony, and make the minor 7ths into half diminished chords, like this:

Now you’re working with the idea and making it your own, which is good, but if you leave it there, you’ll be stuck with playing variations on a group of notes. That’s where understanding the underlying harmony comes in handy. If you know that the lick is embedded in the harmonic minor scale, you can use that to widen your possibilities.

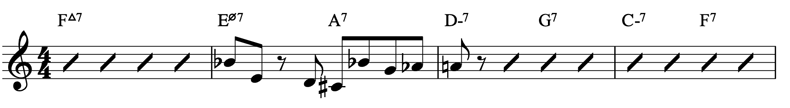

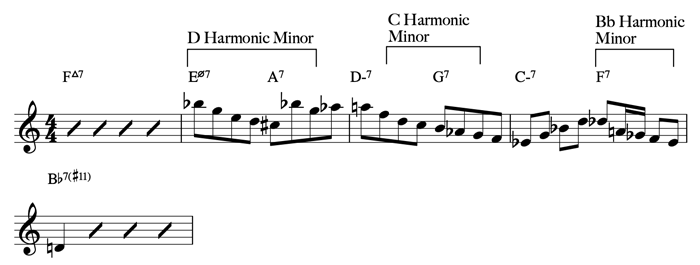

And here’s one more iteration using Parker’s idea as a starting point and making up my own set of lines:

Get the idea? If I can be clear, and find lines that sound good, I can improvise with more than just notes—I can create numerous variations on a simple idea. To return to the language analogy, I know that I need words (licks) to make sentences (lines), and I know that certain words are frequently used. Just because they’re used a lot doesn’t mean I should avoid them. What I want to do is use the words I know to make interesting sentences. In conversation we speak naturally about our thoughts and feelings in the moment. We don’t make up sentences in advance and then repeat them verbatim. Same thing with the language of jazz.

I hope this idea will help you speak the language of jazz more fluently. Feel free to reach out if you have questions about this approach, and happy practicing!

The Jazz Saxophone Book can be purchased at Sher Music, here’s a direct link.

The demonstration videos associated with the book are free and available to the public. You can find them by searching “Tim Armacost and the Jazz Saxophone Book” on Youtube, or following this link.

The videos can also be accessed via www.timarmacost.com