Loren Stillman – Interview and Exercises for Triad Groupings, Cell Development, and Giant Steps

Introduction

Introduction

I have been a fan of Loren Stillman’s playing for quite some time. Recently, I saw Loren posting more videos on Instagram of himself playing tenor – an instrument which I didn’t know he played – and sharing some great practice ideas everyone could benefit from as well as additional content on his Patreon.

I reached out to Loren, who was nice enough to sit down with me and share more about his story, including how he got to where he is today and what projects he is currently working on. For those of you not familiar with Loren Stillman, here’s a quick bio to get you up to speed before we dive into the conversation.

Biography

- Saxophonist and composer, Loren Stillman, continues to contribute to the realm of modern jazz, earning praise from esteemed publications such as The New York Times, Downbeat Magazine, Jazziz, Jazz Times, and National Public Radio.

- Loren studied with some of the greats such as: Lee Konitz, David Liebman, and Ted Nash to name a few.

- Loren has an extensive performance history spanning the United States, Europe, and Japan, his portfolio includes collaborations with The Charlie Haden Liberation Music Orchestra, Paul Motian Trio 2000+2, Carla Bley, John Abercrombie, and Michael Formanek: Ensemble Kolassus, among others.

- Early in his musical journey, Stillman received accolades such as two Outstanding Performance Awards (1996 & 1998) and the Rising Star Jazz Artist Award (2004) from Down Beat Magazine. A scholarship recipient at both the Manhattan School of Music (1998) and The New School (2002), Stillman further solidified his standing by reaching the semifinals of the 2002 Thelonious Monk Saxophone Competition.

- In recognition of his compositions, Stillman was honored with the CMA/ASCAP Award in 2005, followed by the ASCAP Young Jazz Composers Award. His original recordings, including “Going Public” (Fresh Sound 2013), “Winter Fruits” (Pirouet 2008), and “It Could Be Anything” (Fresh Sound, 2005), have received critical acclaim from prestigious outlets like The New York Times, New Yorker, BBC Jazz Review, Jazz Man Magazine, and Downbeat Magazine.

- Recent accolades include the 2022 National Endowment for the Arts ARPA grant, solidifying Stillman’s position as a distinguished artist. He proudly represents Vandoren and Conn-Selmer as an endorsed artist and imparts his expertise as a Lecturer of Advanced Saxophone at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School in the Global Jazz Department, in addition to his international teaching engagements.

Interview

ZS: Who introduced you to the saxophone? What got you excited about playing the saxophone and why?

LS: My late uncle Michael introduced me to the saxophone when I was about seven years old. Working for IBM in the Bay Area, he pursued an amateur saxophone career while also publishing poetry. As my father’s brother, both shared a passion for complex music, especially classical composers. Consequently, our home was always filled with music. When I began playing the saxophone, I was introduced to iconic artists like Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis through vinyl records. It was their sound that immediately captured my attention, even if I didn’t understand the language and systems they were working with.

ZS: As you have progressed and continue to develop your own sound and technique, who did you try to emulate the most and what was your process?

I always sought to emulate all the musicians I discovered along my musical journey. Whenever I came across a new artist or album, I would play along, sometimes transcribing entire solos or simply trying to capture the sounds, energy, and communication I felt. Growing up near New York City, I was fortunate to have access to a vibrant live music scene in the city’s clubs. Hearing live music always reinforced what I had learned from records. I also got to meet jazz legends based in NYC, so I was lucky to have a wealth of knowledge at my fingertips.

ZS: Who were your saxophone influences growing up and have they stayed the same or changed over time?

LS: During high school, I had the opportunity to hang out with and learn from jazz luminaries like Joe Lovano, Lee Konitz, Dave Liebman, John Abercrombie, and Manny Albam. We’d have sessions and lessons together. These influential figures profoundly shaped my perspective on music, saxophone technique, composition, and development of a unique sound. While their expertise sometimes went over my head, I recognized the special and distinctive quality of what each was doing. I admired their individuality and used it as a guiding principle in my musical journey.

ZS: When it comes to teaching & practicing, what is your process? In what ways have you approached practicing that you have found to be the most beneficial?

LS: I continually challenge myself to explore the core questions: Why does this practice matter? Will it foster my creativity? Can this concept or routine enrich my artistic expression? As musicians, we encounter numerous frameworks to master, making it imperative to inject creativity into these structures. I really enjoy guiding individuals to break free from these confines, while stressing the importance of approaching familiar ideas with renewed creativity. The perceived strictness of jazz pedagogy sometimes leads us to believe there’s a one size fits all approach. While mastering both technical and artistic skills is crucial, there exists a realm of interpretation and imagination to be applied to fundamental and advanced musical systems. If we were to express this mathematically:

Systems + Creativity = Innovation, or (S + C = I)

Innovation, to me, results from the fusion of systems and creativity. A thorough grasp of the existing systems serves as our primary and indispensable stepping stone toward innovation.

ZS: As you have played throughout the states, Europe, and Asia, what similarities have you seen in terms of the audience engagement and what differences have you seen?

LS: It’s disheartening to see a growing trend of American musicians seeking greener pastures abroad in pursuit of a more fulfilling life. Jazz, in particular, stands as America’s music, yet it often finds itself overlooked and its practitioners seeking recognition elsewhere. Personally, I relocated to Köln, Germany in 2019, drawn by the promise of a more sustainable career, especially with the abundance of live performance opportunities in European countries. Despite encountering some cultural hurdles, the move proved beneficial until the pandemic upended our lives.

In response to the challenges posed by the pandemic and the necessity of maintaining connections with students globally, I turned to platforms like Patreon. This not only allowed me to stay in touch with students but also provided a means to continue fostering musical dialogue and education.

I’ve been fortunate to have opportunities to share my insights through guest lectures at various music schools worldwide. Patreon serves as a valuable tool for me to stay connected and engage with those eager to deepen their musical understanding and discourse, regardless of geographical boundaries.

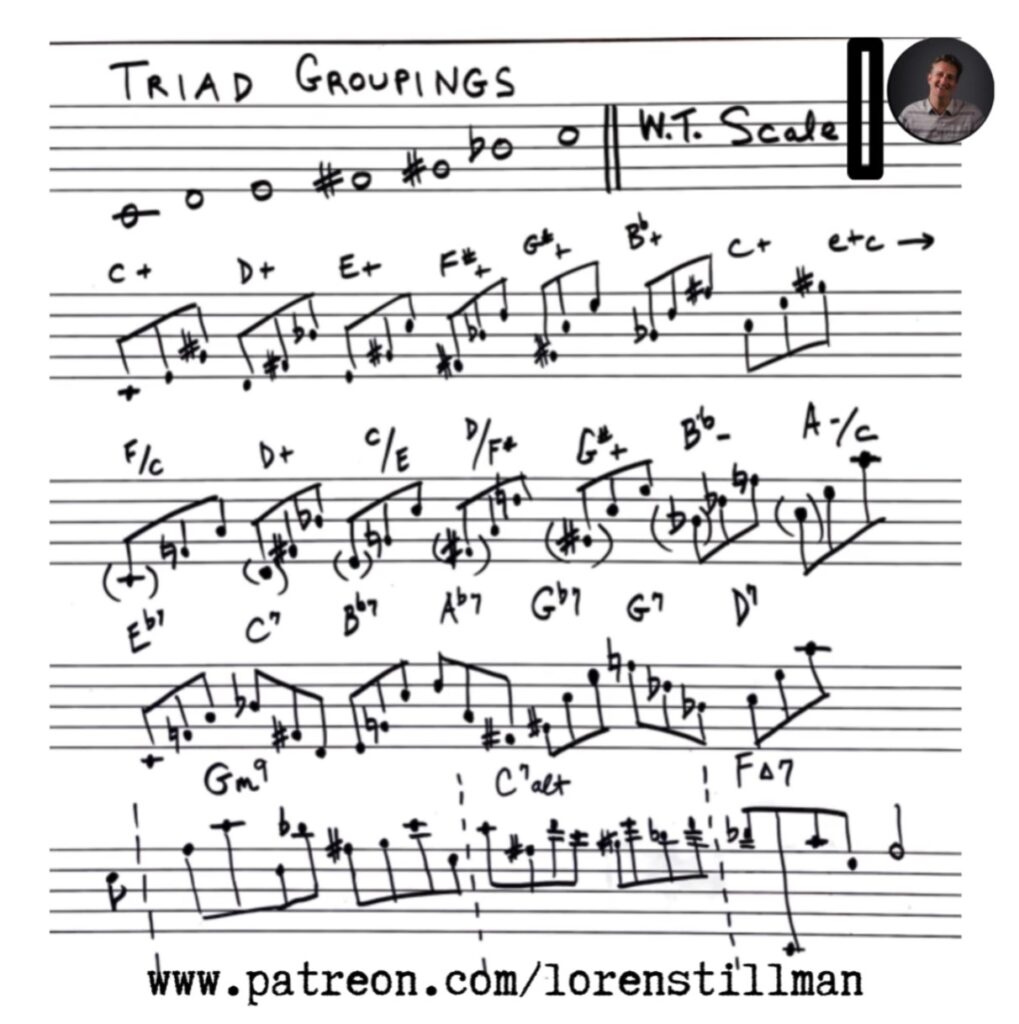

Exercises Taken from Loren’s Patreon

- Choose any of the twelve notes as your starting point.

- Determine the sequence in which this note will be utilized across sequences (e.g., #9, 3, 5, 6, 7, 11, b13).

- Select the voicing for this note, such as top, middle, bottom, etc.

- Generate numerous variations and combinations of single-note sequences. (For brevity, I’ll provide an example using 11 notes.)

- Randomize the connections between notes (e.g., 1-11, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 3, etc.).

- Perform both ascending and descending sequences.

- Design a range of multi-note voicings, such as four-note groupings, five, six, seven, etc., that not only harmonize with your selected note but also outline the function of the chord you’ve formed.

Giant Steps: Macro and Micro Analysis

A few months back, I shared a video of myself playing John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” in a duo setting with the app Drum Genius, using a loop by Jack DeJohnette. Today’s post was inspired by a request from a Patron who expressed a reluctance to play “Giant Steps” in public or on gigs, citing its challenging nature and reliance on patterns and sequences. I empathize with this sentiment, as “Giant Steps” can indeed feel like a daunting obstacle for many musicians.

In response, I wanted to offer alternative perspectives on approaching the harmony of “Giant Steps” that might free up improvisers from feeling confined by Coltrane’s solo choices and encourage them to see the piece from a broader perspective. Explore these ideas and find what resonates with you.

- One approach, which I’ll refer to as the “Micro” approach, involves navigating from one major chord to another in an augmented sequence by emphasizing dominant V-chord relationships. (try Giant Steps with tri-tone subs)

- Another approach is to view the harmony as if a single scale or double augmented scale can be applied seamlessly throughout the entire form.

- Taking it a step further, a third possibility involves combining both approaches—Micro and Macro—by connecting the major chords through a mixture of the double augmented sound.

Here, I’m exploring a five-note minor pentatonic cell. I’m taking a systematic approach by creating ascending and descending sequences following specific cycles. I’ve attached my written examples of ascending and descending patterns using whole tone, tritone division, and augmented cycles. My ultimate goal is to internalize the shape and gain the ability to manipulate it improvisationally. The final two examples are improvised, and I aim to transcribe my thought process and analyze the connections formed during the improvisation.

ZS: What are your thoughts on the importance of the equipment? Do you find yourself changing much or sticking with the same gear?

LS: Finding the right gear is crucial, but it’s equally important not to become overly fixated on it. The goal is to discover equipment that feels natural and comfortable – be it saxophone, mouthpiece, reed, or ligature – and then avoid excessive tinkering thereafter. Personally, I’ve made only a few changes to my mouthpieces and horns over the years. My priority is to get the gear that facilitates the production of overtones effortlessly and smoothly, without excessive manipulation of the sound. I prefer to be in control of my instrument, especially advocate for my own sound, rather than the gear to dictate the approach.

Equipment

Alto:

- Saxophone: Selmer Mark VI

- Ligature: Ishimori

- Reed: Vandoren Java 3

- Mouthpiece: Selmer Soloist & Vandoren V16 A9

- Case: Wiseman

- Neckstrap: Just Joes

Tenor:

- Saxophone: Selmer Mark VI

- Ligature: Ishimori

- Reed: Vandoren Blue Box 3

- Mouthpiece: Selmer Soloist G+, Otto Link, Marantz Slant Legacy HR

- Case: Wiseman

- Neckstrap: Just Joes

Connect: