Transposition Techniques for Generating Unlimited Improvisational Ideas

As jazz saxophonists we are always contending with the challenge of “originality.” Like most saxophone students, I started out practicing from method books and transcribed solos, but eventually realized that I was not going to stand out as a player, or feel creatively fulfilled, if I only practiced what everyone else was practicing. I had to build my own improvisational language. Now, much of my musical development comes from writing and practicing my own patterns for improvisation. When I’m especially engaged with this process, these patterns become exercises in technique, ear training, tone, composition, harmony, and aesthetic. The more time I spend writing and practicing my own material, the deeper my connection feels to the sounds coming out of my horn on the bandstand. I hope to shed some light on my process here.

As jazz saxophonists we are always contending with the challenge of “originality.” Like most saxophone students, I started out practicing from method books and transcribed solos, but eventually realized that I was not going to stand out as a player, or feel creatively fulfilled, if I only practiced what everyone else was practicing. I had to build my own improvisational language. Now, much of my musical development comes from writing and practicing my own patterns for improvisation. When I’m especially engaged with this process, these patterns become exercises in technique, ear training, tone, composition, harmony, and aesthetic. The more time I spend writing and practicing my own material, the deeper my connection feels to the sounds coming out of my horn on the bandstand. I hope to shed some light on my process here.

The way I construct patterns for improvisation is grounded in some very simple methods of altering notes and rhythms. The method I’ll be discussing today is a technique you probably already know: transposition.

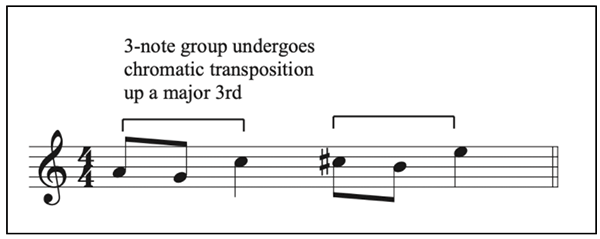

For the purposes of building a unique jazz vocabulary, I like to think of transposition in two distinct ways, chromatic and diatonic. When a note or group of notes undergo chromatic transposition, it is shifted by a set amount of half steps (Example 1). The end result is a note or group of notes higher or lower than the original, but with the exact same “shape” as the original.

Click here for a more readable and printable PDF version of the written examples below.

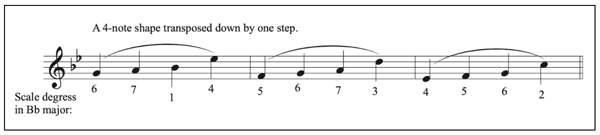

When we transpose a note or group of notes diatonically, it is transposed to a new position within a specific key or scale. Instead of moving by half steps, the notes move by scale degrees, resulting in a slightly different shape than the original due to the asymmetrical series of half steps and whole steps in our major scales (Example 2).

These two methods of transposition make up a large portion of jazz vocabulary. For instance, you may have noticed that Example 1 is a quotation from “Giant Steps” and Example 2 is a quotation from “Autumn Leaves.” But just on their own, these methods of transposition are musically limited. They become creative challenges once you try to find ways of combining them.

Nested Methods of Transposition

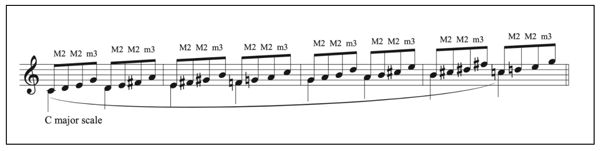

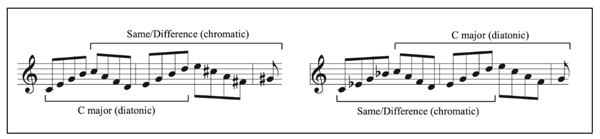

Example 3 is a simple demonstration of chromatic and diatonic transposition unfolding simultaneously. Each four-note group contains the same intervals (major 2nd, major 2nd, minor 3rd), making them all chromatic transpositions of one another, but the first note of each group outlines an ascending C major scale (Example 4). This is a chromatic transposition nested within a diatonic transposition, and to my ears it has just enough unevenness and unpredictability to be musically interesting, and a little more human. For example, the first three groups transpose up by whole step, starting on C, D, and E, respectively, while the fourth, starting on F, has only been transposed up by a half step.

This nesting technique works just as well when a diatonic transposition is nested within a chromatic transposition. You can also easily increase the complexity with additional layers of transposition, or by using other methods of transposition based on melodic minor or pentatonic scales.

Overlapping Methods of Transposition

In addition to these nested chromatic and diatonic transpositions, I also structure my patterns around areas where chromatic and diatonic transpositions overlap, allowing me to transition from one to the other. I can move smoothly between diatonic “in” harmony and chromatic “out” harmony, and find opportunities to surprise the listener by confirming or subverting expectations set up by these patterns.

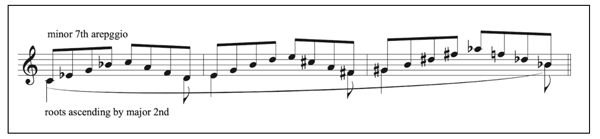

Example 5 is a pattern of chromatic transpositions I call “Same/Difference.” Minor seventh arpeggios transpose up chromatically by major 2nd, and within this ascent the individual arpeggios alternate between ascending and descending (Example 6).

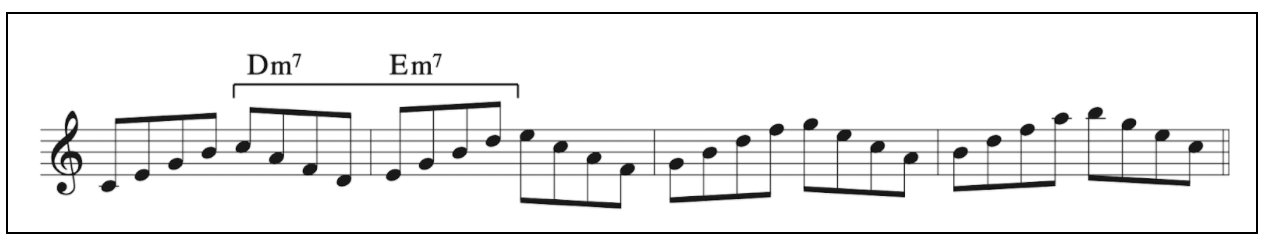

Example 7 shows an equivalent pattern but with diatonic transposition.

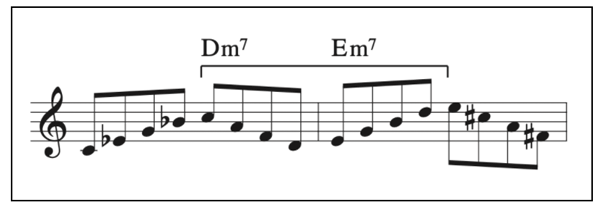

In the key of C major, these seventh arpeggios still ascend by step, while their individual direction alternates between ascending and descending. But because this is a diatonic pattern, its arpeggios are not always minor 7th chords. In one spot, however, this diatonic pattern perfectly overlaps with “Same/Difference.” The second and third arpeggios (Dm7 and Em7) are consecutive minor seventh arpeggios a whole step apart. Note Example 8, the first two measures of “Same/Difference,” where these arpeggios occur in the exact same place.

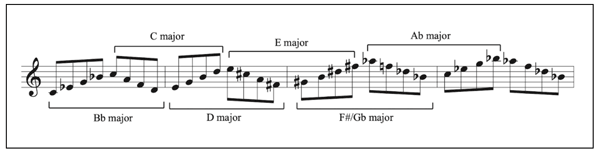

This means you can use these two measures to shift smoothly from “Same/Difference” to the diatonic pattern, and vice versa (Example 9). By this same logic, “Same/Difference” provides access to six different major keys as demonstrated by Example 10, allowing you to apply this chromatic pattern to a variety of chord progressions, or use it to reach more remote harmonic destinations in an organic way.

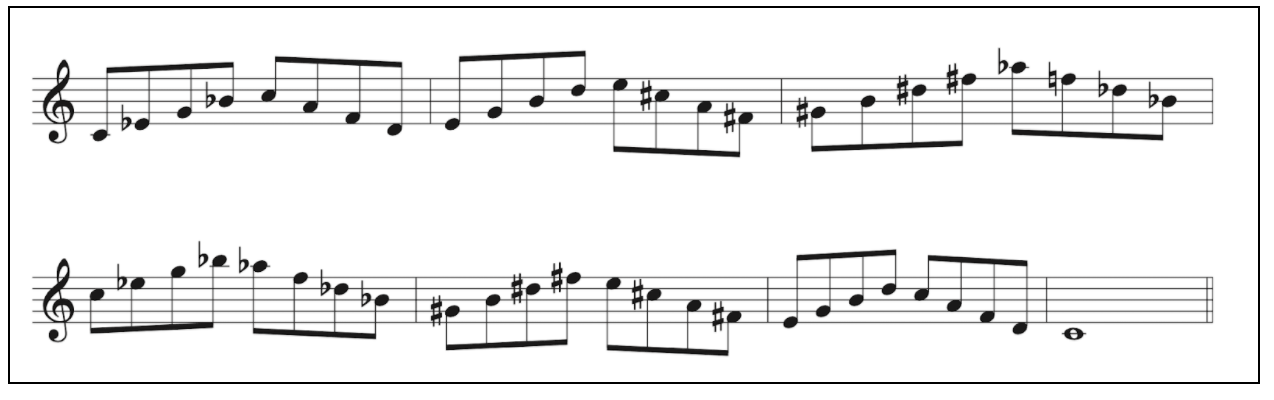

When mixed and matched and combined with strong swing rhythms, chromatic and diatonic transpositions will lead you to some far-out and personal vocabulary (Example 11).

As you become more comfortable with chromatic and diatonic transpositions found in the traditional scale and arpeggio exercises of method books, you should also practice combining them and searching for those meaningful places of overlap. These simple tools of improvisation, when applied creatively, give you access to a complex universe of options in which you will undoubtedly find a planet to call home.

Transforming a Michael Brecker Solo Into Original Patterns for Improvising » Best. Saxophone. Website. Ever.

February 19, 2024 @ 9:25 am

[…] previous article for this website explored transposition as a method of generating new ideas for improvising. With […]