A Saxophonist’s Guide to Building “Killer Chops”

Over the past few generations there has been an exponential increase in the technical capabilities both of professional and advanced student saxophonists. What was once reserved for the premier virtuosos is demanded of every undergraduate-level performer and the list of abilities continues to get larger for younger and younger musicians.

Over the past few generations there has been an exponential increase in the technical capabilities both of professional and advanced student saxophonists. What was once reserved for the premier virtuosos is demanded of every undergraduate-level performer and the list of abilities continues to get larger for younger and younger musicians.

While there have been several books describing individual extended techniques and specific methods to achieve them, the amount of new, comprehensive, technical, and musical material for study at the fundamental level has been quite small. Advanced saxophonists have taken it upon themselves to naturally extend exercises from older texts or borrow material from other instruments and adapt it for themselves. While this is a perfectly fine exercise, and one in which I have participated, there is no good reason for not having a method that reflects current and future technical demands and lays them out in a clear pedagogical format.

The idea for this text came out of a class I taught at the University of Michigan during my graduate degrees called, “Chops.” As I had been experimenting with my warm-up, voicing, and technical work down the hall from Professor Sinta every day, he asked me to start getting his undergraduates doing similar exercises the following Fall. In preparation, that summer I went through every saxophone method available in his office, both from the jazz and classical worlds, and played them through in their entirety, along with several non-saxophone method books from our woodwind colleagues.

Seeing not only the gap between what modern saxophonists were doing and the methods they were using, but also the gap between the rigor and relevance of several other instrumental methods and the general lack of such rigor in our own materials, the thought was born to fill this gap and provide pedagogical material necessary to the current repertoire.

Hopefully this will continue to challenge and inspire the next generation(s) of saxophonists.

An Overarching Approach Laid Out in Two Parts

In my book, Chops 1, the focus is on every fundamental area of what we might traditionally call a warm-up. The term warm-up has different meanings for different players in that some think of this as a comprehensive first hour or so of their practice, others think of it literally as a quick set of exercises to get the horn and their chops warmed up but not incorporating extensive technical work. Whichever is the case for you, there are exercises here which will help with the daily advancement of technical ease and fluidity from the simplest of long-tone exercises to the most advanced chromatic technique. Too often it is the case where method books merely group every possible combination of notes in several keys and call that an exercise when really it is a mere arbitrary assemblage of pitches. These exercises where chosen for specific purposes which are included with the instructions and which the advanced student will readily identify.

In Chops 2, the focus is entirely on scale patterns and meaningful ways to vary, expand, and develop rotations of scale-pattern practice that are both useful and fun to practice. If you are still working on your scales the same way you first learned them something can and should change. This is one area where many times we are guilty of not being nearly as creative with our practice as we should be. The Scale Pattern listings here will take you through exercises to keep scale practice a useful tool for both written and improvised music.

The Art of the Warmup

Personally, I believe in an extensive warm-up regimen to start the practice day, before any repertoire or etudes are studied, however, how much time is spent on warm-up and technical practice is dependent on a number of factors. Some of these exercises might be somewhat familiar while others will present completely new material. As such, the learning curve for individual exercises will dictate how much time is required of them. For those embarking on advanced study of the saxophone as students or as professionals, it is likely that you have several hours a day to practice your primary instrument. If that is the case, it is recommended that the first portion of your day involve a wealth of Long Tones, Intonation, Voicing, Articulation, Vocalises, and Mechanism.

Practicing these areas first will allow you to find your sound before embarking on practice of repertoire and will also warm-up the muscles needed for healthy technical work in all registers. Proceeding to technical practice, the student should focus on one fundamental area as opposed to attempting to work on all facets of technique in one session. Also, the technique practiced should have some connection with the repertoire/etudes/tunes currently being studied. If your repertoire is largely chromatic or octatonic in nature, diatonic intervals aren’t necessarily the best accompanying technical practice.

However, what is of prime importance is that you work intelligently in manageable chunks of material, chart your progress in these areas, and work closely with your instructor (if you are currently in formal study) to keep your warm-up and technical practice productive and beneficial to your development as an artist. This volume is divided into:

- Long Tones/Warm-Ups: The tempos you choose for long tones should be around 50 – 60 to the quarter note. Unless otherwise indicated, always go for a smooth transfer of notes with no noise or sliding between them. Strive for absolute homogeneity throughout the instrument. Have a clear sound in your mind and vivid tone color imagination before working on any of these exercises and make this concept happen in real time. Using a tuner or drone for many of these exercises is encouraged and both have benefits. However, for more sensitive dynamics and extremes of register a sensitive visual tuner might be more useful. When working on vibrato, choose your tempo carefully so that you arrive at a vibrato speed you wish to use in your regular, musical playing.

- Mechanism: When working on mechanism exercises choose the specific mechanism that is currently challenging you the most. Be patient with these and above all, monitor your technique in these areas for any signs of tension or strain. Working on these microcosms of technique allow you to more fluently work on larger exercises with evenness, especially in the more challenging parts of the horn which are the main focus of this section.

- Voicing Flexibility: As pertains to practicing voicing, I recommend a minimum of embouchure motion throughout the entirety of these exercises, if any. Performing mouthpiece pitch is frequently taught in a fixed/static manner, always returning to the same starting pitch (A on alto for classical playing). While that is fine at a basic level, I encourage you to practice starting higher and lower than this pitch in these exercises and not feel beholden to an arbitrary single pitch. Overtone exercises are well-known by now but I caution you to monitor your hand position and tension when working on these. Too often students neglect this and add a bit of strain to the fingers as they struggle with the overtone exercise. Check for signs of this error frequently during this type of practice as well as similar signs of strain in the embouchure.

- Vocalises: A vocalise-style exercise is one in which technique is worked on in a musical fashion to connect the purely technical material worked on earlier in the warm-up with music and repertoire studied later via flexible studies that focus on tone, direction, expression, and also digital dexterity. When working on vocalises, you can initially practice these with a metronome to get them comfortable at a reasonable speed, however once that is set, I would encourage these be practiced/performed in a Romantic fashion with a great deal of rubato and flexibility of time. Allow these technical studies to express and emote (some phrasing suggestions are given in these exercises). Don’t feel the need to do a complete set of these, rather, play through enough to the point where you feel an ease of technique and a natural sense of phrasing emerging in your playing before scale work.

- Articulation: Articulation, like many fundamental areas of performance, involves the very fine coordination of muscles. Like any other set of muscles, they must be exercised not only to maintain strength and endurance, but also ease and coordination. It is recommended that at least some portion of single, double, and triple tongue be practiced every day. Remember that as you attempt faster tempos with articulation, go for greater relaxation in the muscle. A tense muscle does not move quickly, gracefully, or reliably.

- Scales, Intervals, Arpeggios: Now that you are warmed up for some technical practice, choose what is most necessary in your current playing and also currently missing in your technical arsenal. Always work with a metronome but do not allow all of the great fundamentals of tone, intonation, musical shape, and physical ease you have developed with the aforementioned sections go away simply because a metronome is going and advanced technical material is being learned.

- Cool Down: Finally, allow some time for cooling down before you move on to repertoire and even after you have finished all of your other practice for the day. Choose simple types of exercises to allow you to finish your session feeling comfortable, in control, and ready for the next day’s work. Regardless of how the practice day has gone for you, it is never advisable to finish the day with the most difficult study and in a frustrated fashion. Though these are of course played, you could think of these closing exercises as a quick, final meditation in the practice room before you continue the next day.

Introducing Variety and Utility to Your Scale Practice

Working with patterns is hardly a new concept when it comes to the area of woodwind performance. For generations there have been patterns and scale-forms created to work with jazz improvisation and harmonic progressions, develop characteristic technique for certain time periods of music, and also quite plainly to provide some variety for students.

However, many of these are not written down or transmitted effectively via demonstration or suggestion. Thus, if there isn’t a tangible bit of material, let alone a course for the student to work from, they become easy to ignore and the student returns to the original scale form they had already learned. This leads to the other primary pedagogical reasons for the practice material I wrote for Chops 2:

- There is a persistent notion that there is one primary form of a scale, that being: starting from the bottom and going through the top register and back. While this may have been the first way that you encountered scale work, it certainly should not be the continuing way you practice your scales throughout your studies and is in no way the, “primary form.” Learning a key, mode, or chromatic construction in just one way does not build the types of connections between your fingers and brain, as well as between your technical work and its benefits to your performance of repertoire, that you would wish from advanced study.

- Frequently students work scales and technique up to a certain tempo, gain some good speed and dexterity, and then feel they have gotten all they can from that scale. It’s important that you work with a variety of patterns in rotation so that either through all of your scales or just on one scale, you can focus on dynamic direction, single and multiple articulation, contrasting articulation lengths, intonation, slow fluidity and connection, extended dexterity, and control. Working scales up with a metronome to comfortably fast speeds is still a goal, but certainly not the only goal. Precision creates speed, not the other way around.

An Example of Pattern Formulation

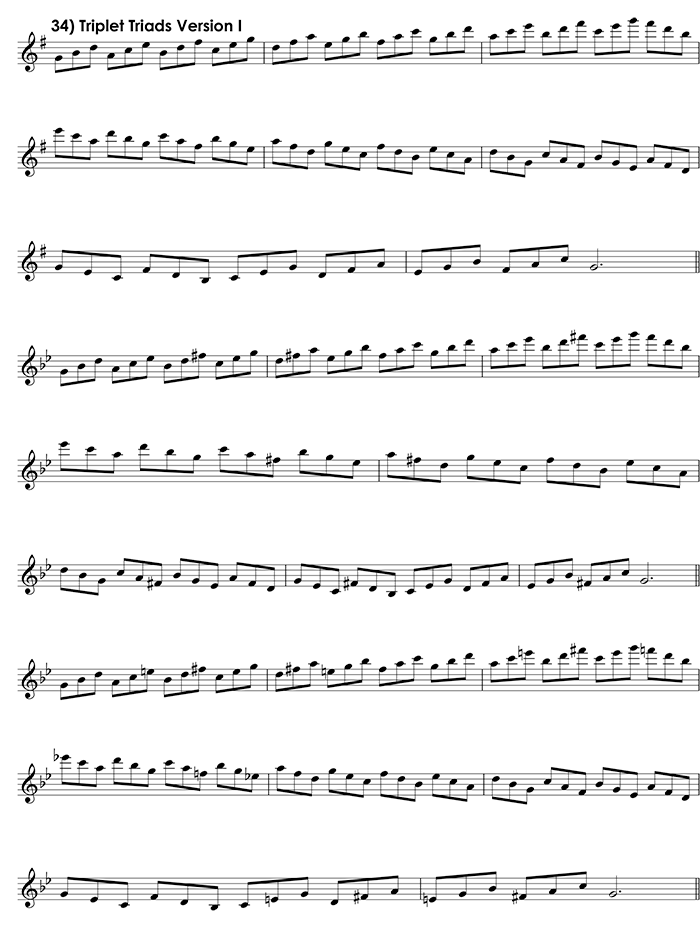

One of the many ways to formulate a pattern is to divide it into its representative chords starting on each note of the scale. The example triplet pattern provides all of the triads found in the standard scales. Further patterns also explore 7th chords as well.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD A MORE READABLE PDF SAMPLE OF THE SHEET MUSIC BELOW.

Pattern Example from Chops 2

Tempo

When it comes to tempo, take any exercise at a relaxed and comfortable tempo to start, mindfully repeat and vary them, and set clear goal tempos at which time you can check off that pattern (for now) and move on. For myself and my students, anywhere between the equivalent of 16th notes at 132 – 150 with a quarter note pulse makes for thorough understanding and useful dexterity. Feel free to have higher or lower tempo goals for each; the most important skill to be learned here is variety and flexibility, not relentless speed.

To Read or Not to Read?

Another aspect of practicing patterns that I would like to address is the use of having them written down, as they are in this volume, versus having a template and working from one example in one key for all of the other keys/modes.

When I was originally introduced to using patterns in early jazz lessons, I was told very clearly that you don’t use the sheet music and need to be able to make the pattern transformations across keys happen entirely in your head. In my later studies with many more complicated patterns, I found I had greater success by having the pattern spelled out as I began to work on them, and then I would gradually work away from the page as I got more comfortable and faster with them.

Having taught hundreds of students at this point and worked through the entirety of the patterns you see here; it is abundantly clear that there is not one way of using these that cuts across all student/performer types. Thus, my recommendation would be to use these first few patterns and rotations to figure out what is most helpful to you.

Generally speaking, if you are looking to add to your technical arsenal for use in improvisation or any performing that does not involve sheet music then working away from the page as soon as possible is the most beneficial. If you are looking to refine the eye – mind – finger connection, then using the spelled-out patterns for a longer period will be more beneficial. Also, if you feel like your upper register is the most challenging or the slowest part of your technique at the moment, working with the page will be most beneficial for the aforementioned connection between what you see and what your brain interprets for your motor skills. For performers of all types, the ability to rotate patterns without the sheet music in front of you is a great skill to develop and one that upon completion of this book you will have developed. Also, for performers of all types, the skill of making every register and its fingerings have the same depth of connection in your mind and motor skills from top to bottom is a necessary attribute which will benefit greatly from the use of these written-out patterns.

Four Unique Approaches to Using Chops 2

This next section is geared towards those who are actually working through the Chops 2 book, but even for those who don’t own the book, the following approaches are likely to be valuable pointers towards an effective method of developing technique.

Section I: Scale Rotations

Though this is perhaps the most basic way to vary your scale-work, it is the most vital to do before progressing. These rotations deal with starting and ending each full range scale on the tonic note but in different octaves each time to achieve fluidity throughout the range, no matter the starting point. Work to achieve dynamic consistency as well and don’t have one particular register that is always practiced at the same dynamic. I would recommend a period of at least a couple of months be spent with this mode of practice (using the full range scales listed at the outset) before any further patterns are practiced. This command of register and key will be crucial to later success with further variation. Then proceed to the variations in how this rotation is developed with the metronome and rhythmic placement. Having worked through this series, you have effectively placed every note of your scales on every part of the beat.

Section II: 30-Day Scale Cycle

Using the skills developed in Section I’s repetitions, now it is time to vary your scale work in every possible fashion, while still working with the original scale form as a base. In each method listed here, the timeframe is 30 days from start to finish. There are 30 variations provided, and the 30 scales used are: 12 Major, 12 Combined Minor, 2 Wholetone, 3 Diminished, and the chromatic scale. There are essentially three ways to work with this rotation and I recommend them equally, perhaps, one to be accomplished after the others. First, you can play every variation every day with the same scale throughout. Thus, you will play the same scale thirty times! This allows for a direct introduction to the variations. The second method is to play through all the scales on a single variation each day. This allows you to get through all your scales on a daily basis while at the same time more gradually introducing you to the variations. Finally, there is a different scale on a different variation every day. Some sample charts as to how these days would develop are provided here. This third method is the most varied method on a daily basis and as such, I would recommend be used last. However, in all cases, at the end of 30 days you will have worked through all of your scales in nearly every possible fashion.

Section III: 42 Diatonic, Wholetone and Diminished Patterns

Here we have ever more demanding scale patterns that focus on the primary diatonic scales as well as the wholetone and diminished scales. These are all constructed purely melodically to incorporate as many useful configurations of notes as possible. At the outset, scales are rapidly worked through on a measure-by-measure basis, others focus on one key area for greater lengths of time. You may find – at least at the start- that it is helpful to have the music in front of you but then move away from it and make the pattern transformations happen in your mind, if that works for you then please do so. Some students plainly learn these more thoroughly with the music in front of them right to the finish. As mentioned earlier, set a goal tempo and timeframe with which you will be working with each pattern. Once you feel you have a consistent and well-learned handle on each pattern, check it off and continue through. Budget a greater amount of time the further you get through these.

Section IV: Chromatic Groupings

Obviously, the possibilities for chromatic patterns are nearly endless. Here, I have endeavored to choose some patterns of tetrachords and hexachords that you likely haven’t encountered in any scale book, you will find in more chromatic repertoire, and which can form effective examples for your own further develop of unique chromatic patterns. For those already working on repertoire with a great chromatic emphasis, feel free to add one of these patterns in to your current work with the previous sections. Thus, this final section need not be practiced last and in fact will be more beneficial if worked in gradually with the more diatonic and modal work that precedes it.

Any technical exercise is designed to push your limits but also to make the physical aspect of playing the saxophone easier, and thus, free you to perform even the most complicated of music in the most expressive and natural manner possible. Happy practicing and make these books your own!

The Chops series of saxophone method books are the first complete update to saxophone fundamentals in several generations and are use throughout the world in both classical and jazz studios. Volumes 1 and 2 have been released and deal with individual fundamentals, Volume 3 will focus entirely on saxophone quartet fundamentals.

Both Volumes are available directly from Conway Publications and can be shipped internationally.

For more information and to make any purchases: https://conway-publications.com

≫ https://www.bestsaxophonewebsiteever.com/a-saxophonists-guide-to-building-killer-chops/

April 2, 2023 @ 5:37 pm

[…] A Saxophonist’s Guide to Building “Killer Chops” […]