Add a New Dimension to Your Solos by Using Four-Note Triad Cells

In virtually any musical idiom from the Western hemisphere, major and minor triads are a fundamental building block of melody. From children’s songs, to folk melodies, to European classical music, to Broadway show tunes and more, some of the most highly recognized and easily sung melodies are based upon the color and structure of the various inversions of major and minor triads.

In virtually any musical idiom from the Western hemisphere, major and minor triads are a fundamental building block of melody. From children’s songs, to folk melodies, to European classical music, to Broadway show tunes and more, some of the most highly recognized and easily sung melodies are based upon the color and structure of the various inversions of major and minor triads.

And no less so in jazz. Whether you analyze an early Lester Young solo, or the latest Chris Potter solo, you’re going to find a fair amount of melodic material based upon these triads (though the approach both of these masters employed in using triads is markedly different from one another).

Major and minor triads have a strong tonal quality that lends itself to cogent sounding melodic statements. So if you know your major and minor triads in all their inversions, you already have a great amount of melodic material at your disposal when you improvise a jazz solo.

Triads and the Jazz Language

One of the defining ingredients of the bebop language is the use of diatonic melodic fragments in conjunction with chromatic passing tones. A good amount of these diatonic melodic fragments are, of course, based upon triads.

And in the modern jazz lexicon, the use of triads is prominent: triad pairs, stacked triads, triads with approach notes, enclosures and more.

I’d like to offer here an easy way for you to turn triads into jazz melodies: By converting major and minor triads into four-note melodic “cells”, then connecting these cells by half steps, you can find nearly endless amounts of freely moving jazz melodic ideas. Allow me to demonstrate.

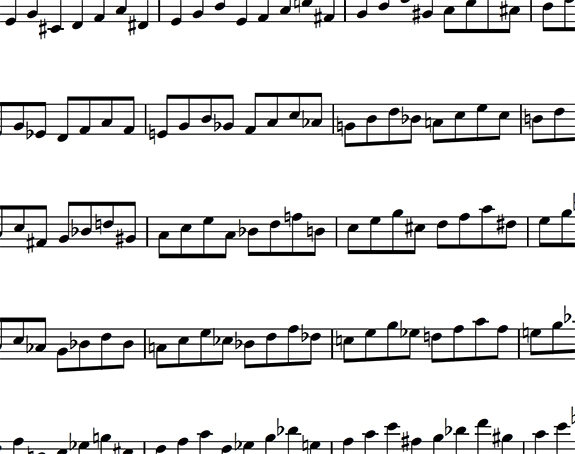

In the example above, I show four different major triads in root position (C, F, Bb, Eb) moving in ascending perfect 4ths (around the circle of keys). I’ve labeled the first triad in relative scale degrees (root, 3rd and 5th of the scales from which they are formed). The other three triads in the example also follow this formula.

Now I’ll take this three-note triad pattern, and convert it into a four-note pattern simply by adding the 3rd of each triad a second time:

Notice here that the triads are now connected one to the other by the movement of a half step lower neighbor “leading tone”. So E is moving up to F; A is moving up to Bb; D is moving up to Eb. In other words, the 3rd of one triad is connecting to the root (the 1) of the following triad. If you were to play this pattern through all 12 keys, you’ll hear a flowing, cogent sounding melodic sequence. It is this connection of the triads by half-step leading tones that help give the line this quality.

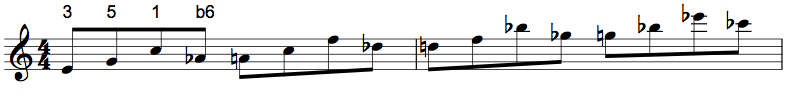

In the example below, I present the same sequence of triads, but now converted into four-note cells that are connected by upper neighbor half-step leading tones:

Two things to notice here: First, there is a movement of two consecutive half-steps between each four-note cell. So in the first measure, G descends to F#, which then descends to F natural (the root of the next triad cell.) The second thing to notice is that the color of each triad has changed because of the altered fourth note. Specifically, each four-note cell is implying a Lydian tonality (because of the raised 4th). Yet if you play the line it doesn’t sound “Lydian” at all. Instead, it has more of the kind of chromatic quality associated with the bebop language.

It doesn’t matter whether the leading tones are diatonic (a note borrowed from the scale from which the triad is formed, as in the first example), or chromatic (as in the second example). All that matters is that the triads are connected via half steps. As you look at the examples throughout this article, you’ll notice that the fourth note of each four-note cell is determined by how one triad connects to the next by means of a half-step leading tone.

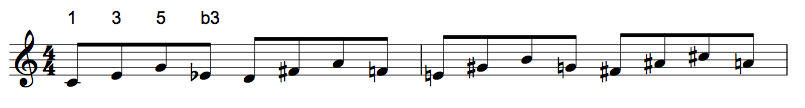

You can of course apply this technique to triads of all inversions. Below is the same chord sequence (major triads ascending in perfect 4ths) , but with a different inversion:

Now here is the sequence from above converted into four-note cells that are connected by lower neighbor leading tones:

In this example, the lowered 6th is being used to connect the 3rd of one triad to the next by a half step. And though the lowered 6th could imply an altered major sound (specifically, an Ab Maj7 +5 in the first four notes, for example) within the four-note cell itself, it actually functions sonically as a lowered 3rd of the following four-note cell (the Ab to A natural relative to the F triad, for example), lending a bluesy quality to the line. (Play through it a bit to hear.)

And here is the sequence with the triads now connected by upper neighbor leading tones:

You’ve probably noticed already that in this pattern, each four-note cell has now been converted into dominant 7th chords (C7, F7, Bb7, Eb7). If you play through this pattern, you’ll hear the familiar melodic quality of playing dominant 7ths “around the circle”.

You can take this “four-note cell conversion” technique and apply it to triads moving in any direction intervallically. Below are major triads ascending in major 2nds (C, to D, to E, to F#), connected by upper neighbor leading tones:

And of course you can also combine chord qualities. Below are major triads descending to minor triads (C major, to A minor, to F# major, to Eb minor) connected by lower neighbor leading tones:

Secondary Triads

Triads formed from each degree of a major or minor scale are sometimes referred to as “secondary triads”. Below are the secondary triads (in root position) of the ascending C major scale:

Lots of melodic material can be found by combining these triads in various ways. Each triad above is already a “four-note cell”, by virtue of the fact that the 3rd of each triad is repeated (1, 3, 5, 3). But when you convert these triads into four-note cells that connect to each other by half-step leading tones, you get lots of “jazz language” sounding melodic movement. Either with lower neighbor leading tones:

Or with upper neighbor leading tones:

As you can see from both examples above, some of the notes have been altered and others remain diatonic (because of the natural half-step voice leading within the scale itself).

This is a fairly simple and intuitive pattern that you can use to convert all of your major scales into jazz sounding melodic material. Here’s a pdf with this pattern put into all twelve keys for you to practice and get into your ears:

Ascending Secondary Triads in All Twelve Keys-pdf

Application Over ii-V7 Cycles

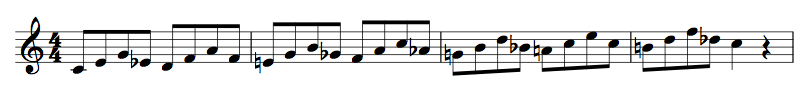

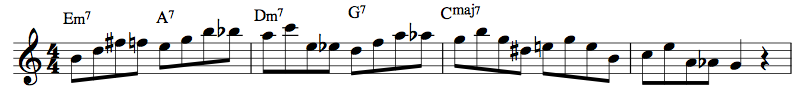

If you were to spend ample time exploring and practicing this “four-note triad cell” technique, you’d find lots of new ways to open up your playing over ii-V7 based chord progressions. Take a look at the example below:

Let’s make a brief analysis of this line: The basic concept is to apply minor triads moving in ascending perfect 4ths over the ii-V7 cycle. The first four-note cell is a B minor triad with an F natural that voice leads it to the E of the next cell (over the A7). The next cell is an E minor triad with a Bb that leads to the A of the next cell. So the B minor and E minor triads are consonant (upper extensions) to the chords, and have added momentum (tension) because of the chromatic passing tones. In the second measure, I use an A minor triad with an Eb that voice leads down to the D over the G7 chord. This D continues over the G7 as a D minor triad with an Ab, which then connects to the G in the third measure (the 5th of the Cmaj7). The rest of the pattern over the Cmaj7 is composed of secondary triads connected by leading tones. Besides having a few altered tensions (the Bb as the lowered 9th over the A7 chord; the Ab as the lowered 9th over the G7 chord), the line also has a flowing jazz quality because the diatonic elements (the triads) being connected by chromatic passing tones. Again, this is a staple ingredient in the jazz language. Play through this a few times and hear for yourself.

This pattern is simple, very basic sounding and familiar. If you’re fairly new to playing over chord changes, it demonstrates an easy way to construct melodic lines with a jazz flavor. Here’s a pdf of the above example in all twelve keys for you to practice and get in your ears:

Minor Triads Ascending in Perfect 4ths Over ii-V7 Cycles-pdf

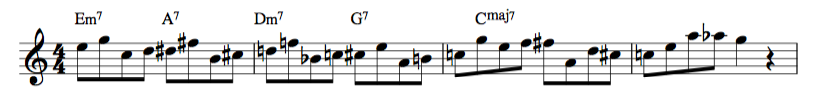

And if you’re a more advanced player, you can find all kinds of new ways to connect triads over ii-V7 cycles using the same technique. Below is an example of a more sophisticated use of the four-note triad cell idea over the same cycle:

In this example, I’m using major triad cells descending in minor 2nds over the ii-V7 cycle to create a more harmonically dense sounding line.

Here’s a pdf of this pattern in all twelve keys:

Major Triads Descending in Minor 2nds Over ii-V7 Cycles-pdf

Further Explorations

You can take this simple idea as far as you like. By experimenting with constructing four-note triad cells and connecting them through their various inversions, moving intervallically in various ways, you’ll discover melodic material from the bebop language, all the way through to modern jazz sounds. By working this way, you’ll become a master of connecting melodic ideas through leading tones, which will add up to you creating long, flowing jazz melodies when you improvise. If you’d like to explore this concept deeply, I’ve composed a very comprehensive and methodical e-book that serves as a playable reference (a thesaurus, of sorts) of all the different ways triads can be converted into four-note melodic cells, and connected by leading tones. Click on the link below to find out more:

Want to Dive Deeper?

Four-Note Diatonic Triad Cells: Comprehensive Studies in Leading Tones

January 8, 2018 @ 4:03 pm

Samantha Sermons

July 31, 2020 @ 9:40 am

Hi!

Thank you for the very useful introduction to triads. I just wonder how different is your approach to that of George Garzone and his TCA.

Sincerely

Marek

July 31, 2020 @ 10:36 am

Hi Marek, I’d say that our approaches (mine and Geroge Garzone’s) have overlapping elements. All I’ve done in this e-book is organize and present the triad combinations with passing tones in a methodical and comprhensive way. It’s kind of a “thesaurus”, in a way. Garzone’s approach is a bit more specific in how he combines the triads (and the triad combination that he avoids), but is more open-ended in how he applies them to chord changes. Hope this helps!

3 Tips For Creating A Cool Melody – Never Nervous

October 27, 2022 @ 3:18 pm

[…] moderately slow. It also comes with a lovely chord progression. melodies that frequently contain a dominant melodic cell or motif. There are melodies that have melodic leaps or a series of melodic […]